I recently acquired a lovely book by my late teacher, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, entitled Wir sind eine Entdeckergemeinschaft (We are a Community of Explorers), published by his wife Alice (Residenz Verlag, Salzburg – Wien, 2017). The book tells how Concentus Musicus Wien started, and mentions the different people in Vienna that were part of the long story of that group. It goes on, through several chapters, to chronologically cover what things they did, where they performed, what they recorded, and it’s lovely to read it and to remember all the fabulous people that I had the honor to meet, work, perform, and record with, way back in the 1970s and 80s.

There’s a chapter about events that happened in 1972. After mentioning music by Monteverdi and Gabrieli, which the Concentus had performed in Vienna and Venice, Harnoncourt says:

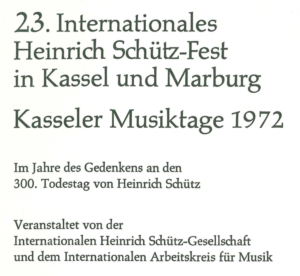

“In September, we go to Kassel, where we are invited to play a Schütz concert at the International Heinrich-Schütz Festival 1972, a new program for us. This time, the Concentus plays in a particular lineup: with 2 violins, cello, dulcian, 2 trombones and harpsichord and singers – two fabulous Tölzer Sängerknaben (boy sopranos), Equiluz is there too. In The Hague, we play the same program, however this time with two Dutch girls instead of the boys, the Instrument Museum in The Hague has to save money …”

So far, so good.

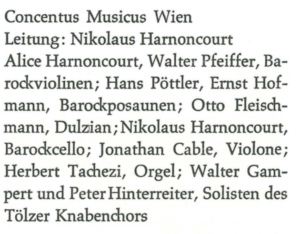

Here’s the thing, though: that’s not the whole story. Besides the fact that the concert in Kassel wasn’t in September, it was on Wednesday, October 4th, 1972, at 4 PM, and the concert in The Hague was on the evening of Friday, October 6th, neither of which is really important – it also wasn’t the complete lineup. In addition to the aforementioned instruments, there was also a double bass (violone) in the ensemble. Here is how I know this:

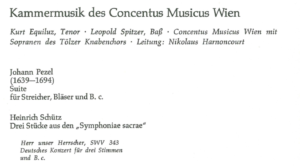

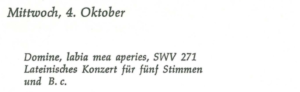

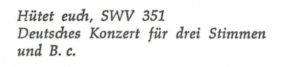

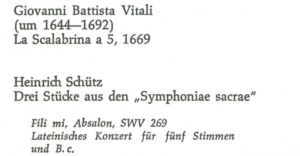

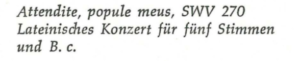

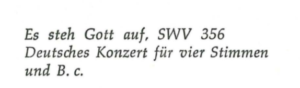

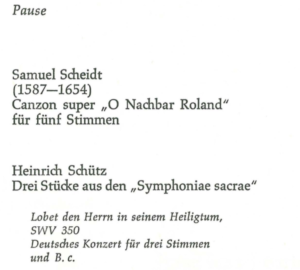

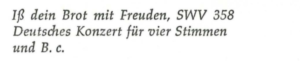

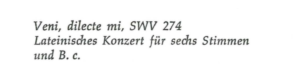

And here is what we did in the concert in Kassel:

This was my very first concert with Concentus Musicus Wien, and it was nothing I could have foreseen or expected. I was amazed beyond belief when Nikolaus Harnoncourt, out of the blue, asked me to do this program with them. We had met earlier that year at a workshop in The Hague, and I was at a Concentus concert several weeks later at Schwetzingen. I arrived there while they were rehearsing, and during a break he just walked up to me and said, “I would like you to do these concerts with us.” I had a hard time believing it, I must have stood there in complete shock with my mouth open for an eternity.

I didn’t travel with the group from Vienna to Kassel: this may be why he doesn’t mention the bass in the lineup, he may have just had notes of the people from Vienna who traveled. At the time, I was studying in Hannover at the Musikhochschule, at a place where there was little to no early music at all – a far cry from so many conservatories today. Anyway, I traveled down to Kassel from Hannover, it was only an hour and a half by train, and there I was. I got there two days before the others, as I wanted to visit the instrument exhibitions, check out the music publications that were there, listen to lectures, hear other concerts, and other such things. I spent those first two nights in a youth hostel – my meager student budget dictated that. Then on October 1st, the others arrived from Vienna, and as part of the Concentus, I suddenly moved from the youth hostel to the four-star hotel where there were reservations for us. Talk about rags to riches – I had never seen anything like it, and I was almost afraid even to touch anything.

I remember being out-of-my-gills nervous before the first rehearsal on the afternoon of October 1st – there were only eight musicians, we all had important parts to play – no room for error, and no place to hide. We started rehearsing the Pezel (beautiful music, by the way), and within a matter of what seemed like seconds, all of a sudden, I was no longer nervous, worried, or afraid: I was doing my thing, I was in my element, and the other musicians, all around twenty years or more my senior, made sure to convey to me, the just turned 24 year old newcomer, that I was an equal to them. They took me under their wings and immediately integrated me into the group.

I was one of them. The most fabulous feeling imaginable.

I remember exiting the concert hall after the concert, down a long stairway towards the exit. At the bottom of the stairs, there must have been a hundred or more people, waiting for us – all of us, even me! – to autograph their programs. I couldn’t believe it, and yet it’s one of the moments in your life that you don’t ever forget. Mind totally blown. The next day, Thursday, we were on a train to The Hague. Friday, we rehearsed there in the afternoon and had the concert in the evening. We said goodbye the next day, Saturday, and we promised to see each other again soon – they returned to Vienna, I went back to my dorm in Hannover.

Then, the letdown. Soon after I got back to school – the winter semester 1972/73 was just starting – I was summoned to see the dean of the string department. I was told, in no uncertain terms, that I was wasting my time with all this early music nonsense – they were actually angry that I had played these two concerts – and that it was high time for me to get on with diligently studying in order to graduate and get a good job in an orchestra somewhere. I already knew that wasn’t going to happen, and I started making plans to leave Hannover and go somewhere else where I could continue down the path that had been shown to me by the experience of the workshop in early 1972, and the concerts in Kassel and The Hague. I knew there would be no turning back, and I was determined to find a way to make a living playing early music, no matter what. I knew I would never be an orchestral musician in the traditional sense. Early music was my destiny, and I was somehow going to make it work.

The next year, 1973, I moved to Salzburg. It so happened that Nikolaus Harnoncourt had started teaching performance practice there, at the Mozarteum. I very happily became his student, and I also got my bass orchestra and solo diplomas at the Mozarteum in 1976 and 1978. Our ways parted – he went on to continue the fabulous career that everyone is familiar with, and I went on to play for many years with musica antiqua köln before moving to France in 1984 to join forces with Les Arts Florissants.

For some reason, Harnoncourt’s and my paths never again crossed for almost thirty-five years, until February 28th, 2014. We were both in Vienna at the Theater an der Wien – he was finishing a rehearsal of Don Giovanni with the Concentus, and we (Les Arts Florissants) were having our last performance of a Rameau opera that evening. I went into the rehearsal room after they finished, and waited a moment. He saw me, welcomed me, and we talked for ten minutes as if we had never been apart. It was the last time I saw him. In December of 2015, when the news of his stepping down from the Concentus became known, I wrote to him, wishing him well. He and Alice wrote back. For me, it was heartbreaking, because we knew it was goodbye.

I am not telling this story because I want to complain about the missing bass (violone) in Harnoncourt’s 1972 recollections. People forget things, they forget other people, they omit things because of an oversight, anything can happen.

In this case, history may have forgotten me, but I haven’t forgotten history, and this is a part of my personal history – and the history of others – that I am happy and proud to share.

Thank you for reading.

Written and added on May 6, 2018

This is extraordinarily beautifully written. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for sharing this wonderful story!

Enlightening. Thank you Jonathan for sharing a part of your life.

Thank you for your beautiful writing. And thank you for taking us with you. Your courage has paid many dividends both for you and for us. Heartfelt Congratulations.

Schön von dir und der damaligen Zeit (u.a.Salzburg) zu lesen

Schön auch von dir zu hören. Vielen Dank daß du dich gemeldet hast.

Gestern habe ich erzählt, wie wir quer durch London gedüst sind mit der Violone in der Cabrio- Ente, 1980?

Ich kann mich vage daran erinnern … wie war das nochmal? Kannst Du mir auf die Sprünge helfen?